Paper Read: Seven Thoughts On Running Big Money For the Long-Term by AQR (2009)

Corey Hoffstein, host of one of my favorite podcast Flirting with Models, said if he could only recommend one article on investing, it would be this.

This paper, written by Cliff Asness (co-founder of AQR) in 2009, was updated from its prior 2007 version for hopefully obvious reasons. While addressed to institutional investors, I thought it'd be interesting to read from a retail perspective.

A belief of mine is that large investors face the same pressures as small investors do, but bigger. The former experience them more acutely and will take concrete steps to handle them, whereas the latter might not even distinguish them from the ups and downs of the market, but they still affect PnL. This is where retail investors can find value in reading accounts from institutional investors regardless of the difference in AUM.

1.) Embrace Risk - In the Long Term, You'll Need It

The old adage is there's a higher reward for taking more risk. The more risk you can (comfortably) take on, the higher your returns will be over time.

Underlying this is a tenet, merely implied in the paper: every institutional investor is in it for the long run, regardless of whether they run short-term or long-term strategies. This arguably applies to retail investors as well.

2.) To Survive in the Long Term, Brace Yourself for the Short-Term

Pretty self-explanatory. When disaster happens, make sure it doesn't kill you (where "kill you" means you are forced to permanently change how you run your portfolio).

Retail arguably has an edge here operations-wise: if you're in an investment team (like the paper describes) you have to convince your colleagues and upper management (maybe even your investors) about tanking short-term risk, whereas with retail investing you only need to convince yourself.

3.) Diversify Your Market Risk as Much as Possible

Market risk - beta - will drive the lion's share of your long-term returns. So you should allocate the risk in your portfolio, not the capital.

The "best" portfolio for you performance-wise may not have the risk level you want or need. To adjust this you can:

Add leverage to that "best" portfolio (if you're more risk tolerant)

De-lever by adding cash (if you're more risk averse)

There will be practical limits in optimally doing either of the above steps. For example do NOT add significant leverage to significantly iiliquid strategies. But getting close to where your portfolio has that structure is desirable to manage beta.

4.) Seek Out Alpha in the Land of Beta

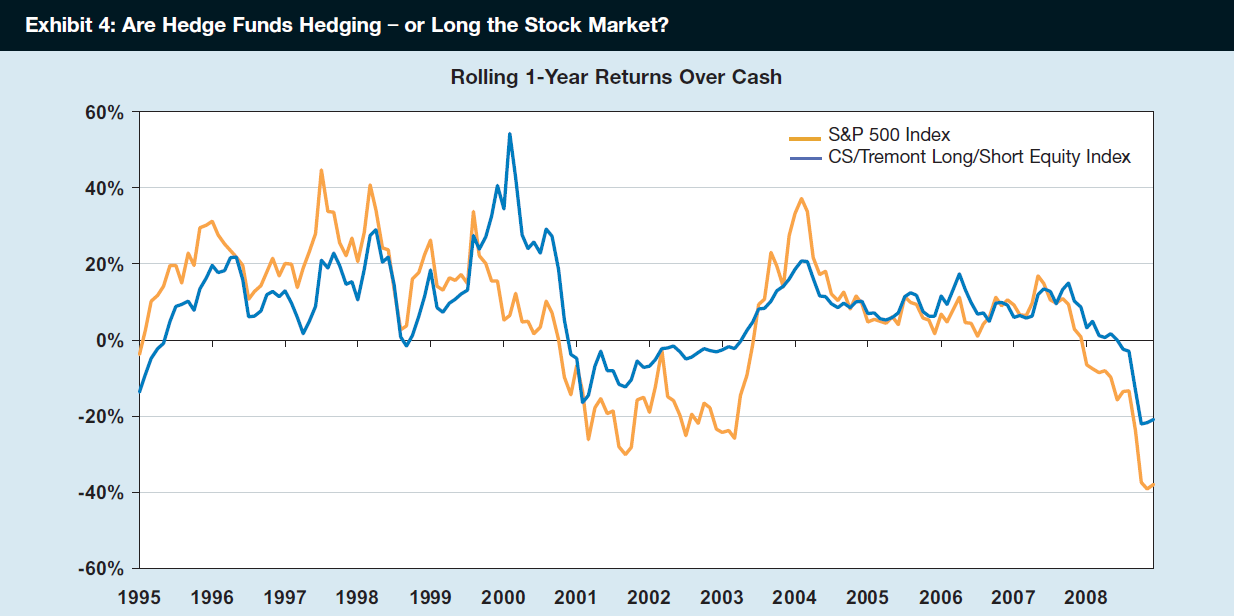

Active management is NOT alpha, but a form of beta. Cliff loves this chart from the paper, showing hedge funds are more correlated to the market than they realize.

Any return source that is not already in your portfolio is potentially a source of alpha to you. This could be active management, or it can be an asset class (like commodities, etc) uncorrelated to any assets you hold.

There is no difference between adding an asset class and an active management strategy with the same expected risk/return as said asset class. But the former is probably cheaper (no management fees) & has less blow-up risk.

These additional asset classes are a new source of beta, but in a portfolio context they could behave like alpha (hence the title).

5.) Add as Much Manager Alpha as You Can Find, Net of Fees and Factors

This is not that relevant to retail, but the idea is, per the previous section, it's hard to find active managers that truly have alpha (net of factor risk and fees). So if you do find one, allocate for that alpha instead of "we want X dollars for (any) active managers".

6.) Don't Be Afraid to Take a Contrarian View

Again, not that relevant to retail, the problems described (accepting long down periods for the right asset classes/active managers which aren't capacity constrained) only applies when investing huge HUGE sums of money. Retail is more flexible than that, and likely can't bear an asset with multi-year drawdowns like institutional investors can.

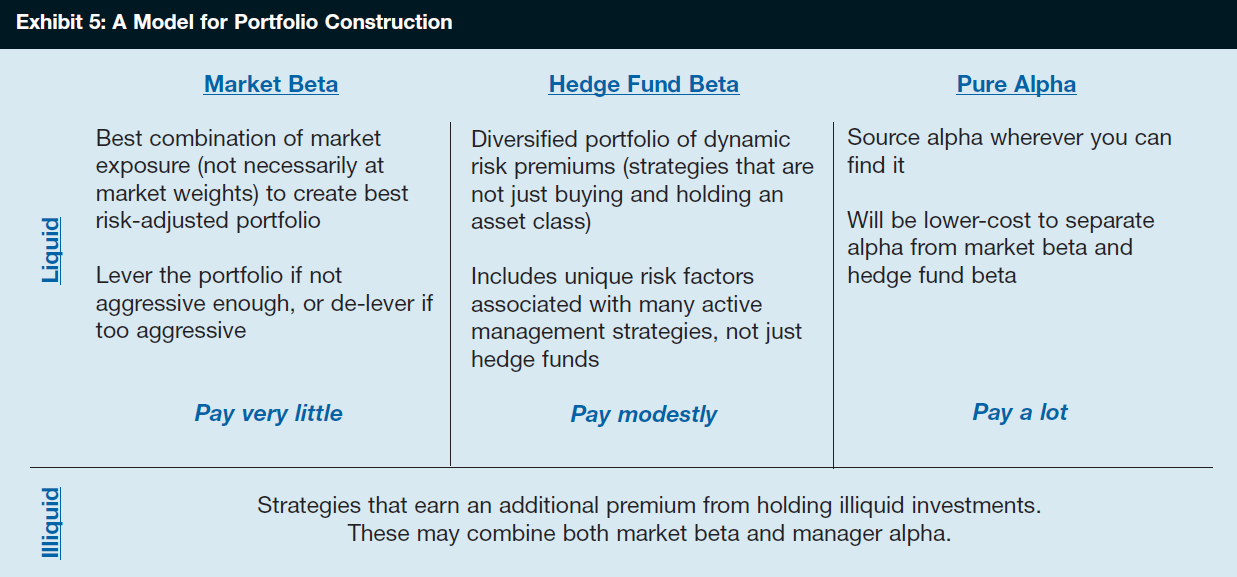

7.) Be Innovative in Combining Market Beta, Hedge Fund Beta and Alpha

Combines ideas from the previous sections into a coherent portfolio model. The chart tells it well.

Summary of Recommendations

And finally, the paper's own summary of the whole thing.